‘Never let a good crisis go to waste,’ Winston Churchill famously remarked. Famed for leading the Allied opposition to Nazi aggression during WW2, Churchill was no doubt aware more than many of the political value of crises, particularly to anyone looking for some scapegoat or other onto whom to shift the blame for the undesirable effects of policies for which they themselves were responsible.

‘Never let a good crisis go to waste,’ Winston Churchill famously remarked. Famed for leading the Allied opposition to Nazi aggression during WW2, Churchill was no doubt aware more than many of the political value of crises, particularly to anyone looking for some scapegoat or other onto whom to shift the blame for the undesirable effects of policies for which they themselves were responsible.

Churchill’s commentary would seem to have continuing relevance. Last Sunday hundreds of thousands of people around the world marched in protest, demanding urgent government action on climate change. And with good cause; if the science is anything to go by, it is clear that the world faces a very real crisis that demands robust, thorough and above all else permanent change.

This week, in the aftermath of these global protests, we see the Abbott government responding to a crisis — not the one the population is clamorous about, unfortunately, but a crisis all the same. One might perhaps rejoinder that our government is functionally able to respond to crises per se and that, for that fact alone, we should be grateful. Then again, if they are capable of responding to crisis, why not addresses the crisis the public is actually protesting against?

One wonders. If the Abbott government is capable of responding to the climate crisis, but does not, then how can one conclude otherwise than that it does not want to? One might also enquire as to why Abbott might respond to some crises, crises that relatively few are clamorous it respond to, while neglecting those against which so many tens of thousands of Australians rallied over the weekend in protest.

For an answer to these and other questions, we might refer to the work of Stanley Cohen, author of the first sociological study into the phenomenon of moral panics. In his groundbreaking study Folk Devils and Moral Panics, published in the early seventies, Cohen described a process he referred to as “deviant amplification” — the process by which a scapegoat was constructed as part of a broader campaign of blame shifting, a campaign that manifest socially as a moral panic under conditions of high drama.

In the example Cohen studied, the political establishment targeted members of youth subcultures for ‘deviant amplification’ and demonization in the aftermath of a series of violent disturbances at Southern England beachside resorts such as Brighton, Margate and Clacton in the late 1960s. These disturbances, he concluded, were the result of widespread anger and alienation amongst working class youth brought on by social and economic marginalisation — a phenomenon consistent with government policies favouring the upper classes.

Naturally, respectable society saw things dramatically differently at the time; the disturbances, exaggerated and sensationalized in the media, were typically reported as riots, and treated by the general public as such. As Cohen demonstrates, however, much of the moral panic that arose in reaction to the so-called thugs, louts and degenerates bringing British society to its knees was instigated by those who had been the recipients of the same government policies that had marginalised the youth thus angered and alienated.

Predictably enough perhaps, those who had lead the reaction against the disturbances did so in the main by demonising and stereotyping those involved — namely, ‘hooligans,’ ‘delinquents’ and ‘troublemakers’ who terrorized children and the elderly, and marauded around like ‘mutated locusts wreaking untold havoc on the land.’ The official response was predictable enough — a heavy-handed police response and draconian laws restricting freedom of movement around the affected areas.

At no point during this moral panic and the official response that followed did anyone attempt to grasp the root cause of the problem of the beachside disturbances, such that they might be remedied and avoided in future. In hindsight of course, and with the benefit of five decades and half a world of distance, we can adduce without much trouble that it was the marginalization of the youth that was at issue.

Of course, such an insight was totally unwelcome at the time, when policy towards the issue was being determined. As Cohen illustrates, however, the function of ‘deviant amplification’ in the context of beachside disturbances in England during the 1960s was to create a stigma around segments of the population, more or less superfluous to the needs of business, whose assertiveness and potential for rebelliousness presented a threat to the status quo.

Similarly, it was to re-impose the legitimacy of power structures brought into disrepute in the final analysis as a result of the actions of those who controlled them. Those orchestrating the panicked reaction to the disorder created in the final analysis by government policy were creating scapegoats out of its victims by themselves playing the victim.

In casting the working class victims of government policy as demons and enemies of British society, the instigators of the panic were simultaneously defending themselves as Britain’s defenders; in the polarised atmosphere of the time, one could not oppose them without being seen to give aid to the evildoers. Thus, through what we know today as moral disengagement, did they effect the shifting of blame and shirk responsibility for causing the problem.

The obvious parallel we can draw between the scenario Cohen describes in his magnificent work on moral panics and the state of Australian society today rests then in the resistance to social change from those who create policy and those who benefit from it the most. One might argue that Muslims today are subject to the same dynamics of deviant amplification as the alienated youth of five decades ago in England (much less to say the numerous other minorities demonised, scapegoated and persecuted throughout history).

Just as the spectre of juvenile hoodlums provided a pretext to blame-shift the socially-destructive consequences of government policies five decades ago onto the victims, so to today does Tory scare-mongering over Islamic fundamentalism and terrorism provides a pretext to blame-shift the socially-destructive consequences of government policies onto the victims today. Similarly, just as questions about the causes of the disturbances back then were sidestepped, so too are any about the causes of geopolitical disturbances today.

That being the case we never ask ourselves if there is any relationship between the groups springing up around Mesopotamia now and the training the United States gave groups like the Taliban (who Ronald Reagan called ‘the moral equivalent of the founding fathers’) and others such as Osama Bin Laden during the 80s, in the name of resisting aggression from the former Soviet Union. Chalmers Johnson for one seemed to think there was.

Likewise we rarely if ever questions the modern configuration of states in the region around what’s subjectively known to the West through our imperial gaze as the Middle East, though the fact is well established that the British redrew the map after the First World War to group together disparate ethnic groups like Sunni and Shia Muslims — a strategy that worked perfectly from the point of view of enabling them to divide and conquer, though not one that was ever likely to guarantee peace nor stability.

The West’s history of intervention in Middle Eastern affairs would seem to suggest we are culpable for a good century of instability and oppressive, authoritarian governments. Though mere facts such as these might seem like goods thing to keep in mind when deciding whether or not to pontificate about ‘their’ morals versus ours, they would likewise seem to be the first to be relegated to what George Orwell described as the ‘memory hole’ in the process of constructing the new Terror Scare to which our government seems committed.

One could say the same about other questions, such as why Islamic fundamentalism exists in the first place, and what the role was between the wars of aggression waged in antiquity by the Christian forebears of the West in the name of freeing the Holy Lands from the Infidel and the polarization of certain quarters of the Islamic religion against its enemies. Again, questions that are conveniently forgotten amidst the process of deviant amplification — though of course the victims never forgot, even if the bully did.

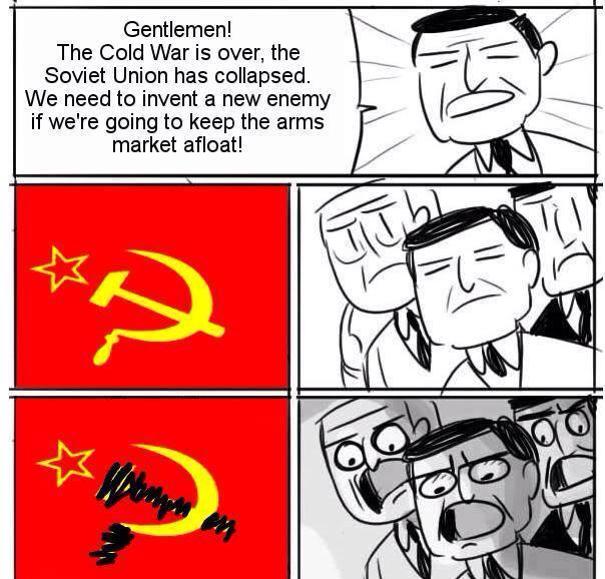

Of course the parallel between Australia today and England in the 1960s is only one of many that are becoming harder and harder to ignore; the first Terror Scare in 2001 invited comparisons with Cold War anticommunism and of course the Red Scares of 1947-54 and 1919-20, which in turn invited the kinds of comparisons with the phenomenon of witch hunting Arthur Miller made in The Crucible, which he used to critique the McCarthyist scare-mongering of the 1950s and unstated assumption that if you thought for yourself, the communists won. Students of propaganda have examined the use of moral panic as an instrument of statecraft and the deployment of deviant amplification as means of blame shifting and scapegoating for some time in this respect.

This fact is of great significance and relevance in the present moment, as the actual crisis we are experiencing over the worsening state of the climate crisis and the patent unwillingness of our government to do anything about it becomes more and more acute. If the anti-communist panics, like the panics over alienated working class youth in the south of England, provided a pretext to blame-shift the socially-destructive consequences of government policies onto the victims by equating rebelliousness, nonconformity or disturbance with malevolent destructiveness, then so too do persistent terrorism panics, or terror scares.

Here we reach the crux of the problem. The climate crisis is one the government can deal with, but clearly does not want to. Tony Abbott has already said he doesn’t accept the findings of 98% of climate scientists. The findings of climate science are not convenient to the profit margins of the mining and energy conglomerates that dominate the Australian economy, and with it the political system. The Tories did not spend 48 billion dollars gold-plating the electricity grid to go and then take action on climate change.

What we have then is not only a climate crisis, but also a crisis of freedom. Freedom and representative democracy have always had an uneasy existence, not least because the latter was built on a foundation in Australia of mass dispossession, genocide and economic privilege. That fact notwithstanding, freedom is not growing, but shrinking; it is becoming obvious that even the uneasy relationship representative democracy has had with freedom historically is not enough to ensure issues as important as climate change are getting the recognition they deserve.

This conclusion seems inescapably true than when we consider that what passes for democracy in 2014 Australia is permanent moral panic, based on false dichotomies between national security and supposed threats built upon the dynamics of deviant amplification, moral disengagement, the manipulation of subjective emotional prejudices and historical amnesia. As for all authoritarian governments who hate and fear the popular will and fall back on propaganda tricks to defend privilege from the winds of change, they are the oldest tricks in the book.

Ben Debney is a PhD candidate in International Relations at Deakin University, Burwood.

Discover more from Ben Debney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.