The 2014 remake of Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is a great movie. It also features a sequence which, from the point of view of the history of international relations, provides a surprisingly accurate metaphor for the use of moral panics as instruments of statecraft.

In this particular sequence we see two processes at work: one sociologists refer to as the production of deviance, the foundation of moral panics, and the other of ‘disabling the mechanisms of self-condemnation social psychologists refer to as moral disengagement.

Spoiler alert for text that follows.

The Planet of the Apes franchise tells the story of the rise of a civilisation of apes who gain sentient levels of intelligence as a result of scientific testing of a viral drug that wipes out most of humanity. In Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, the apes are free of the testing lab and building a community in the aftermath of the collapse of human society. They are lead by Caesar, who hopes to avoid conflict with the humans who remains as he knows that war will bring devastation on his own community regardless of whether the apes win or lose.

Another of the troupe, however, Koba, has suffered greatly at the hands of humans and has a chip on his shoulder. When humans working near the ape community establish contact with Caesar, he and Koba fall out and eventually fight, only stopping when Caesar defeats Koba, who he deigns not to kill on the grounds of the community axiom that apes should not kill other apes. With his ire aroused against Caesar, Koba takes the opportunity one night to engage in a little production of deviance and scare-mongering about the threat humans pose to the ape community to pursue his own agenda.

After killing two guards of the town armory and Carver, one of the group of engineers working near the ape community, Koba steals the latter’s cigarette lighter and shotgun. He uses Carver’s lighter to set fire to his own home.

Mmm, just like the Reichstag.

Caesar, oblivious to Koba’s scheming, has his attention on his family who he’s rather keen to see not killed in a unnecessary and pretty pointless war.

Until he hears something and, turning his head…

Spies Koba crawling around in the scrub beneath where he’s standing.

With the shotgun stolen from Carver, who is now dead.

Which he points at Caesar..

..and fires, striking Caesar in the shoulder, who staggers back in shock..

Koba looks at him, as if to say ‘if you’re not with us you’re against us.’

Caesar looks back at him as if to say, ‘What brand of crack have you been buying from every military adventurist in the history of human civilisation?’

Everyone else looks up as they hear the shot echo through the community. The shot that rang around what’s left of the world.

Caesar tumbles off the cliff, past Koba, into the darkness.

In the pandemonium that ensues, Blue Eyes, Caesar’s son, retrieves the gun.

Here begins the production of deviance.

Koba picks his moment of return well and jumps into the fray. ‘Humans killed Caesar.’ The audience, of course, knows better.

Predictably enough, this produces uproar as the flames from the fire Koba started spread, metaphorically and literally.

The humans in the community run for their lives as apes find the cap Koba planted near the fire after stealing it from Carver.

Koba incites the hopping-mad apes. ‘Fight humans! Avenge Caesar!’

..and assumes the role of leader.

Adding a little personal touch for Blue Eyes’ sake along the way.

And so it begins.

So easily do the apes succumb to panic in this scene that they no less stop to check whether Caesar is actually dead (which he isn’t), than they do to see if Carver was the one who fired the gun (which he couldn’t have been, because he was actually dead).

By shooting Caesar with Carver’s gun, leaving it for Blue Eyes to find and then inserting himself into the middle of the apes when the tension levels start to rise, Koba is able to produce deviants out of the humans by manipulating the panic to shift the blame for the shooting of Caesar onto the humans in the city whom he demonises as assassins.

Koba is further able to play the victim of human aggression, blame the victims (the humans he is about to attack) of his own, and abjure his own responsibility for the situation by disguising his own role. In these actions we not only see the intimate relationship between the production of deviance and moral panic, but also that which exists between the dynamics of moral panics and the mechanics of moral disengagement.

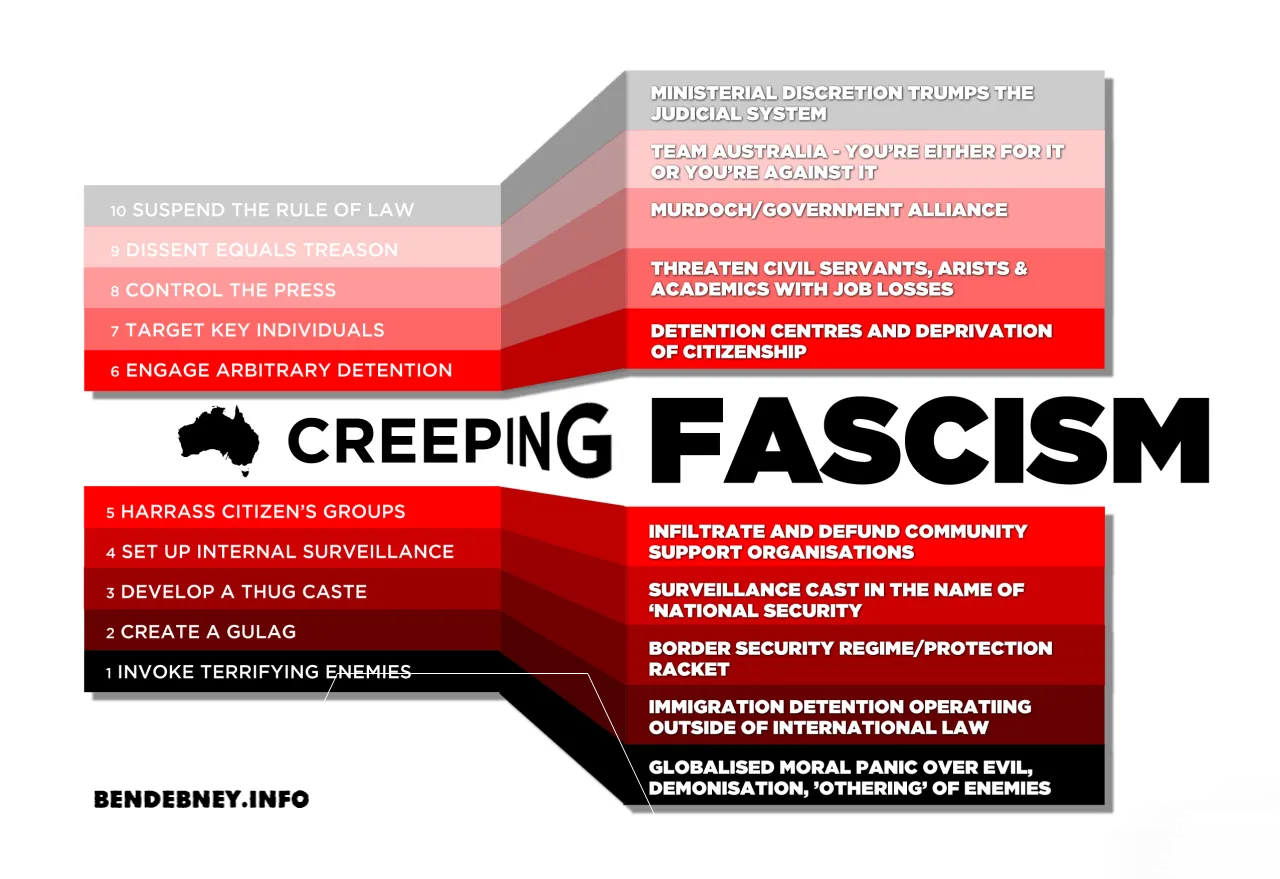

Such are in evidence in reactions to numerous crises throughout history, not least of which being Bush’s response to the 9/11 attacks, which likewise displays all the same dynamics. In responding to the crisis with the logic of ‘questioning our foreign policy means the terrorists win,’ Bush produced deviants by introducing a narrative of terrorism that focused squarely on non-state actors and bore little resemblance to the defining characteristic of actually-existing terrorism: that is it essentially driven by states (primarily the US and its clients; quelle surprise).

Furthermore, in his scare-mongering over terrorism, Bush demonised every muslim on the planet by making terrorism seem like a specifically Islamic problem — thereby holding them collectively responsible for the actions of a few (as if every Christian on the planet should likewise apologise for the actions of Anders Brevik). He played the victim by claiming the terrorists were jealous of American freedoms (the last remaining few of which he proceeded to undermine with the Patriot Acts), blamed the victims by holding former US client Saddam Hussein responsible for the actions of terrorists from Saudi Arabia, and disavowed responsibility by sweeping the history of US meddling in Middle Eastern affairs under the rug.

The same is also arguably true about the ‘domino theory’ at the core of the Cold War, Hitler’s response to the burning of the Reichstag, Stalin’s response to the assassination of Sergi Kirov, Trotsky’s response to the Kronstadt Uprising and Johnson’s response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident, to name but a few (and we haven’t even left the 20th century yet). How many examples can you think of?

Discover more from Ben Debney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.