William Purdue conducts a survey of terrorism in a variety of forms, though differing from mainstream studies of terrorism insofar as, rather than focusing on terrorism from below, he focuses on terrorism from above, on official state terrorism. In so doing he argues that official state terrorism is far more pervasive and destructive than the kind that tends to occupy the forefront of the popular imagination. As the title of his book suggests, he challenges not only the official mythology that focuses solely on terrorism from below and tends to define it entirely in such terms, but also the ideological narratives states put forward to justify ‘counterterrorism.’ The later, Perdue maintains, is little more than state terrorism using the victimhood fallacy as a pretext — the ‘domination through fear’ to which the title refers.

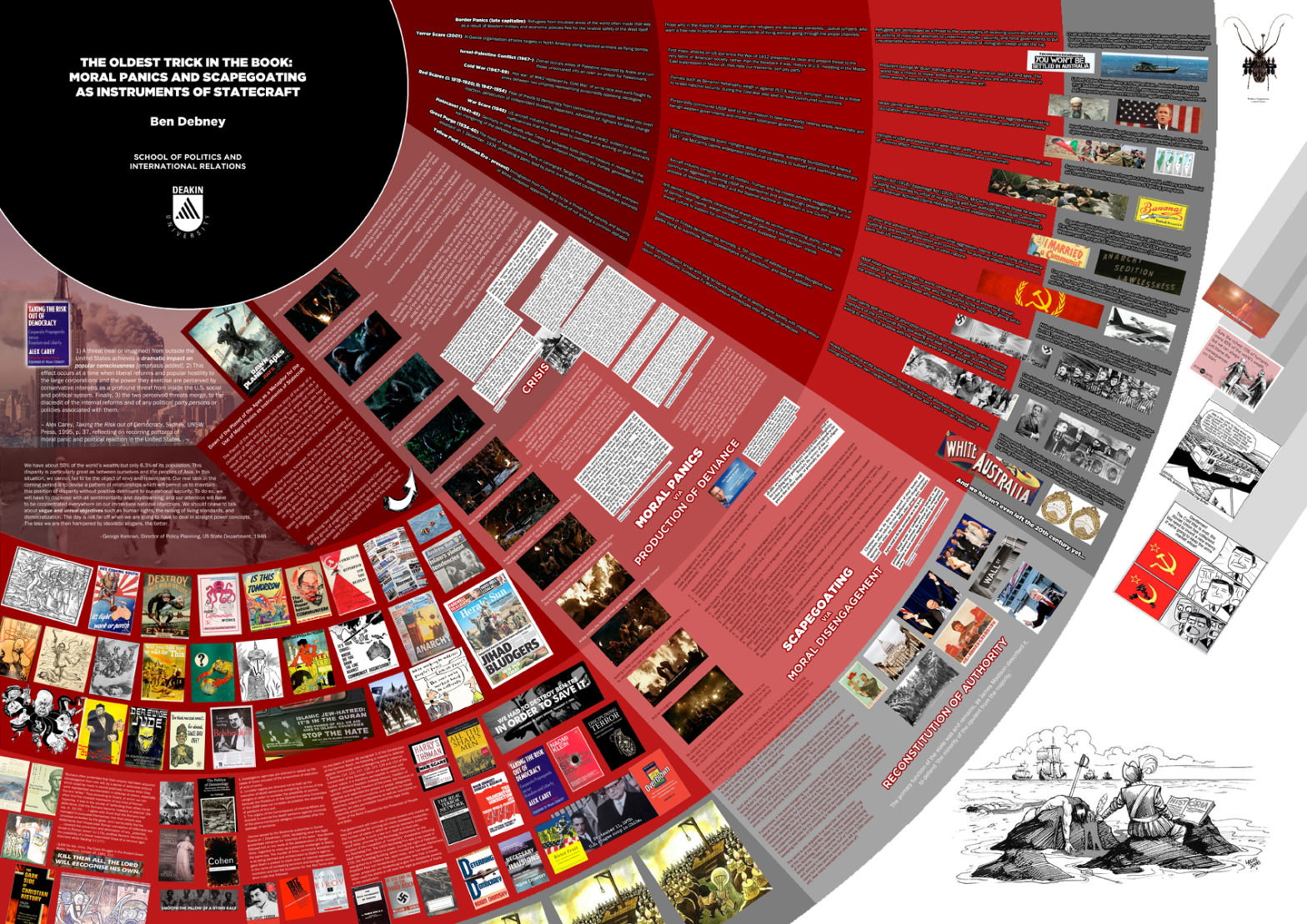

In support of this thesis, Perdue points out that the traditional or conventional mythology surrounding terrorism, such as those contained in Claire Sterling’s The Terror Network, present a distorted point of view that filters out the terrorism of regimes (which he makes a point of distinguishing from administrations) and focuses solely on the violence of non-state actors. These he notes are demonized through the time honoured process of the production of deviance, applying double standards by which the violence of non state actors is condemned while the violence of states is taken to be legitimate as a matter of definition, and one that requires no further commentary or explanation. The function or purpose of this process is, Purdue argues rather convincingly, social control.

Perdue’s critique of conventional terrorist mythology serves in general to perform the same function as Oplinger’s critique of the process of deviance production behind moral panics in particular and demonology more generally. He links the demonization of resistance to U.S. colonialist expansionism and imperialist military adventurism through labeling of indigenous resistance as terrorism to the similar convenient labeling within the U.S. itself of those who dare to question, criticize or otherwise actively oppose the global agendas of the elites who set the national foreign policy. Terrorism, he argues, is a smear that defames those political beliefs or very existence presents inconveniences to the architects of U.S. foreign policy and of ‘excluding those so branded from human standing’ — a fact that, as we have seen from other writers, prepares the ground for the moral disengagement necessary to enable the persecution of political opponents through the production of scapegoats, and the reestablishment of conventional political authority thereby.

By way of providing examples to support his hypothesis, Perdue examines the invocation of conventional terrorism mythology in a variety of settings. First and foremost Perdue looks at the mass media, demonstrating how it narrows the confines of debate over the issue. Rather than examining it from points of view that allow for different interpretations of the meaning of terrorism itself, taking into account dissenting as well as conventional standpoints, Perdue shows, the mass media assume the legitimacy of the conventional standpoint as a basic operating discussion, bringing in strategic questions for discussion only to the extent that they take this assumption as a given. Arguments that try to bring the conventional standpoint itself back into the region of debate, that even question the idea that the conventional standpoint is a standpoint and not a fact, are simply filtered out and not given airtime. The result is a propaganda exercise in which a point of view or an interpretation of events is passed off as proven, demonstrated fact.

Another is nuclear terrorism; this is in fact one of the more notable examples. Perdue makes the very good point that very different moral propositions extend from the images of horror and megadeath seared into the collective consciousness from the aftermath of the Nagasaki and Hiroshima bombings at the end of WW2. On the one hand, and on the basis of the assumption however fraught that morality has some bearing on political decision-making, one might anticipate political efforts to cut back the amount of nuclear weapons in the world. On the other is the apparent idea that they should be ‘used responsibly,’ and that the main danger from nuclear weapons derives from retail terrorists getting their hands on them and using them in an attack. At this point, Perdue reminds us that the nuclear stockpile of the United States and its NATO allies in particular constitute a saber to dangle in front of the whole world, which not only makes a mockery of the idea of responsible use, but also provides them with a pretext to intervene and meddle in the affairs of other countries.

Perdue produces another very useful passage on settler terrorism in South Africa. Though events in the decades since this book was first published have rendered this analysis obsolete in a direct sense where the subject is concerned, it retains a strong historical relevance — if for no other reason than for the parallels that can be drawn between the apartheid regime in South Africa and the one in Israel-Palestine. The social and class-based tensions between the white colonists and the black majority in South Africa provide no shortage of opportunities to draw parallels with those between the European Zionists implanted onto Palestine by the British colonial administration and the disenfranchised Palestinian majority. Perdue notes interestingly enough that the apartheid regime in South Africa characterized its struggle against the ANC as a ‘war on terrorism,’ which in the context of the tail end of the Cold War raises some interesting parallels on a number of levels.

Discover more from Ben Debney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.