The following text was presented at the Australian History Association annual conference ‘Boom to Bust,’ organized in conjunction with Federation University, in Ballarat, Victoria, in July 2016.

I would like to personally show my respect and acknowledge the traditional Wathaurung custodians of this land, of elders past and present, on which this session of the AHA conference is taking place. Sovereignty was never ceded.

This paper will examine the anti-Chinese reaction that developed during the gold rushes in Victoria and New South Wales in the 19th century, in the half-century before Federation. Exploring the meaning of this reaction in the context of settler colonialism, I will attempt to ascertain what relationship the racism and xenophobia appearing here had (1) to other racisms manifest during this same period, the most obvious example of which being that directed against the indigenous population, and (2) to the violent repression of the Eureka Rebellion. To that end I will look at a number of what are generally understood to be racially motivated disturbances following in the aftermath of the Eureka Rebellion, and their meaning in the context of the later appearance of the White Australia Policy in particular and European settler colonialism in general. Given the complexity of the issue these comments will inevitably be relatively rudimentary, but I aim to paint a general picture that is more or less convincing.

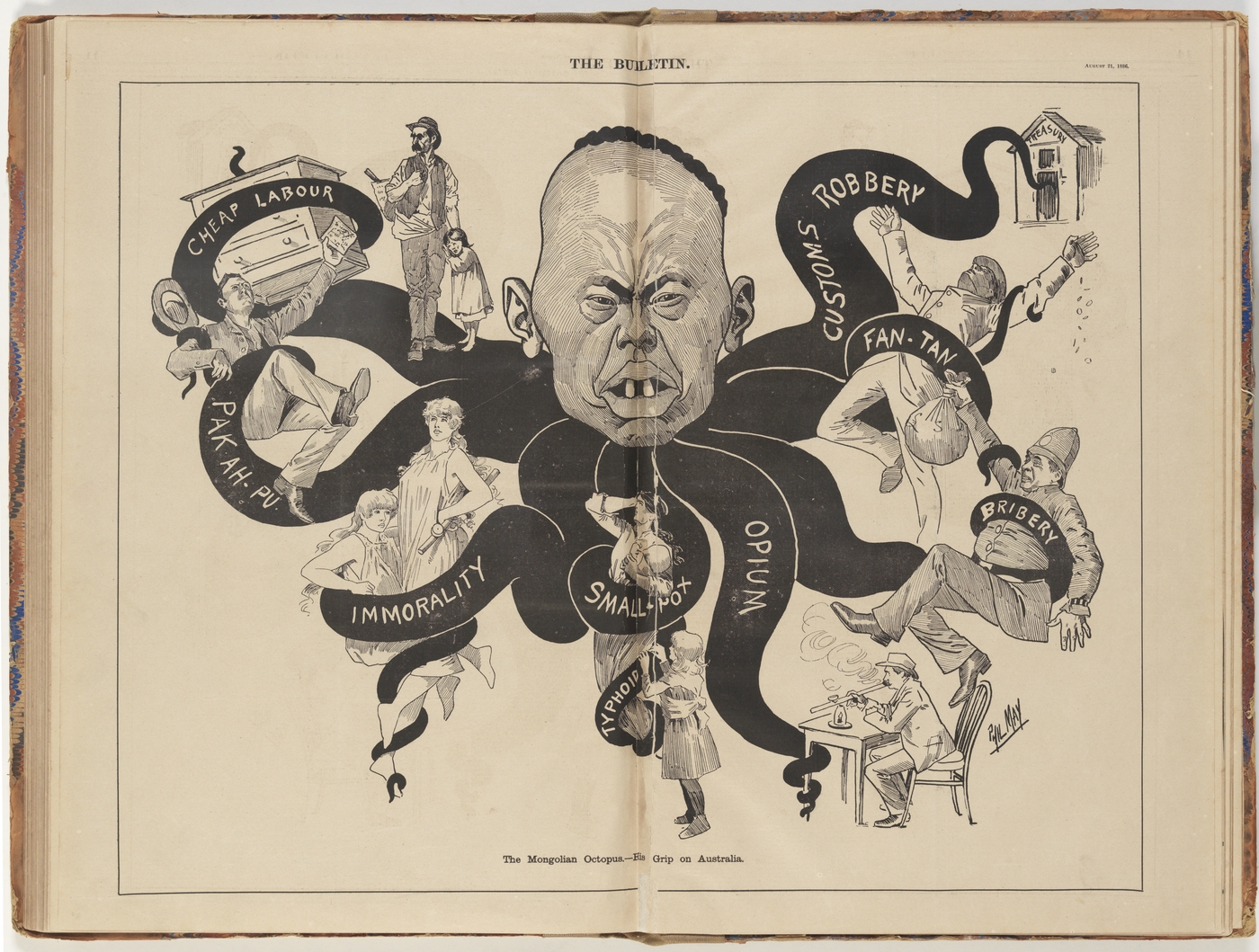

Although Asians had been in Australia as long as Europeans, and possibly longer, as the 19th century progressed their presence became a cause of consternation for white colonialists. Such feelings were perhaps most notoriously expressed by The Bulletin magazine in its 21 August, 1886 issue, which featured a cartoon entitled the ‘Mongolian Octopus’ — a nightmarish figure featuring a grotesque Fu Manchu stereotype and eight tentacles, variously labeled ‘cheap labour,’ ‘immorality’, ‘smallpox,’ ‘opium,’ ‘bribery,’ ‘fan-tan’ (ie. gambling), and ‘customs robbery.’ Said to have a ‘Grip On Australia,’ this monster ensnared a white Australian with each. As this cartoon made unmistakable, colonial bigotry saw Asians as a ‘yellow tide’ threatening to engulf white society.

Conspicuous in the ‘Mongolian Octopus’ image was a paradox that grew out of the conflict between European claims to ownership of the land and their relationship to its original inhabitants. If the ferocious stereotyping of the Chinese population in Australia reflects the discriminatory attitudes prevailing throughout the 19th century, it also reflects a gross sense of entitlement amongst whites, one driven by a fervent belief in white supremacy reserving for itself the sole right to invade and colonize land occupied by others. From the perspective of indigenous Australians, the irony of whites complaining about aliens invading their country and threatening their freedom, livelihood and wellbeing must have seemed bitter to say the least.

That this paradox escaped the creators of the ‘Mongolian Octopus,’ whose moralism wrought hypocrisy as a characteristic feature, tells us something about the racist assumptions behind Australian settler colonialism — ones that remain with us today. Indeed, we find in the attitude of the white majority both to the indigenous population, lately dispossessed of their land, and to Chinese immigrants, common subjective elements that have in the last three to four decades become familiar to researchers in the sociology and social psychology of persecution. The ‘Mongolian Octopus’ is a classic example of the process known to sociologists as ‘the production of deviance,’ a concept based on an acknowledgment of the profoundly subjective basis of the concept of deviance per se; what this simply means is that deviance as a social phenomenon depends on who has the power to define the meaning of the word and impose their own particular definition on popular discourse, rather than on the particular characteristics of anyone thus labeled.

As the defining characteristic and key dynamic of moral panics, the production of deviance is also the basis for blame shifting strategies like playing the victim, victim-blaming and demonizing the victim, refusing to admit responsibility for wrongdoing and articulating a self-defense by refusing to distinguish between criticism of one’s behavior or policies and attacks on one’s person and rights. Recognizing that we rarely reject the idea of morality out of hand, but merely apply it selectively, social psychology classes this particular group of behavioral traits as ‘moral disengagement,’ or the process of neutralizing the conscience and reconstructing scapegoating behavior as morally just. Enabling us to retain the idea of ourselves as moral actors while constructing various pretexts upon which to make selective application of principle for the sake of momentary expediency, moral disengagement forms the basis for an entire spectrum of predatory and discriminatory behavior from labeling and ‘Othering’ to moral panics.

In the context of European colonialism in Australia, moral disengagement is conspicuous in anti-Chinese racism and xenophobia; as such, it bears comparison to that underpinning white invasion. In other words, insofar as moral disengagement characterized the victimization of the Chinese via racist propaganda, this was simply a reflection of its similar role where European colonization was concerned. The doctrine of Terra Nullius sought to hide the consequences of white invasion by literally dehumanizing the prior occupants. As Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze wrote, ‘the Enlightenment’s declaration of itself as ‘the Age of Reason’ was predicated upon precisely the assumption that reason could historically only come to maturity in modern Europe, while the inhabitants of areas outside Europe, who were considered to be of non-European racial and cultural origins, were consistently described and theorized as rationally inferior and savage.’1 This is nothing if not moral disengagement in the form of victim blaming. The reasons for its appearance were not hard to discern; as Sven Lindquist noted, ‘Europeans needed to justify their conquest . . . Most of all, they had to absolve themselves of guilt for the almost total extermination of the previous inhabitants of these huge areas.’2

Where the Chinese were concerned, the psychological mechanics of scapegoating performed a similar function. We get some sense of how and why by looking at a number of disturbances in the half century between the Eureka Rebellion and Federation in 1901. Three events, generally understood to be race riots, stand out — firstly, in Buckland Valley (1857), in Lambing Flat (1861), later renamed Young, and lastly Clunes (1873).3 In the 1850s Chinese immigration spiked; Fetherling claims 2000 Chinese in Victoria in 1854, the year of the Rebellion, a number that climbed rapidly to 17,000 the following year.4 The Argus (Melbourne) described the first of these, the race riot two years after that at Buckland Valley, near Bright, in glowing, almost celebratory, terms:

The Chinese question has entered on a new phase. Exasperated by the perpetual interference of the Celestials with their mining pursuits, and alarmed at the overwhelming numbers continually pouring in upon them, the Buckland diggers of European origin have taken the law into their own hands. On Saturday a large body of the latter collected, attacked the Chinese in their tents, drove them out, set fire to what was inflammable, and literally consumed their habitations and their stores. Pursuing the miserable Mongolians down the river, each of their encampments and its tenants in its turn was served in the same way, until some fifteen hundred Celestials, trembling and panting before their pursuers, evinced their manhood and their courage by fleeing before two or three hundred angry members of the Anglo-Saxon race.5

The Argus goes on to say that the rioters destroyed over 750 miner’s tents, looted and burnt Chinese stores to the tune of £2,000, reduced the newly built Temple to smouldering ashes, and caused numerous serious injuries, though was unsure as to how many of these were fatal. A few years’ difference and three or four intervening riots later, on the other hand, palpably diminished its ardour for blood. Where the Lambing Flat riot of 1861 was concerned, such was the brutality exacted on the population of Chinese miners that the correspondent for The Argus was impassioned to defend the Chinese in the aftermath, incensed not only at the ‘atrocities’ committed against them, but also the lawless mob behavior that continued in the aftermath of the breakdown of social order. ‘Our accounts from Lambing Flat,’ he wrote,

have excited the deepest compassion in the mind of every humane man. Whatever prejudices may exist against the Chinese as a people, or however strong the opinion in favour of their exclusion, we presume no one would stand up and vindicate the conduct of those rioters who have disgraced the digging population — disgraced the name of Englishmen, which we imagine they have usurped and have brought reproach upon human nature itself. If such conduct as they have pursued can find advocates and apologists, we can only say that all our ideas of progress and civilization must be revoked, and we must confess that we have among us principles as barbarous as any to be found in the darker pages of history, or have been exemplified by the basest portions of the human race.6

The New South Wales Government dealt with this problem by passing the Chinese Immigration Restriction and Regulation Act (1861), restricting the numbers of Chinese in the colony. Queensland followed suit in 1877 and Western Australia in 1886. These legislative acts formed the basis for an academic consensus regarding the origins of the White Australia Policy, best expressed by British historian Eric Hobsbawm, who wrote: ‘Certainly the pressure to ban coloured immigrants, which established the “White California” and “White Australia” policies between the 1880s and 1914, came primarily from the working class.’7 On the other hand, as Verity Burgmann has pointed out, the ‘brazen rhetoric of racism strikes a chord in working class experience, because racism has already moulded that experience . . . This reality, created by racist practice, then appears as ‘proof’ of racist ideology.’8 Such a reversal of cause and effect is typical of the kind of victim blaming and playing of the victim we associate with moral disengagement and the production of deviance. As Philip Griffiths has observed, the labour movement lacked the power to impose such a fundamental national policy as immigration restriction.9 If this was the case then it certainly lacked the power to impose a particular definition of deviance on public discourse.

In the case of the 1873 Clunes riot, an interesting perspective in this respect comes from none other than the conservative Quadrant magazine, which in seeking to demonstrate the lack of racial motives in that event for the purpose of challenging the purported propensity of historians to ‘moralise about colonial Australia’s hostility towards Asian peoples,’ inadvertently demonstrates the elite driven nature of deviance production and victim blaming. To this end Christopher Heathcote quotes a passage from the fourth volume of Manning Clark’s A History of Australia (1978) worth relating in full:

When news reached Clunes in Victoria on the morning of 9 December 1873 that numbers of Chinese were about to move onto their field, the miners took instant action. The bellman was sent round the town to alert the diggers of the impending arrival of ‘the leprous curse’. Work was immediately suspended in all the principal mines, and on what remained of the alluvial flats. Public meetings were held at which miners and diggers unanimously resolved to drive the unclean yellow men off the fields. Axe- and pick-handles and waddies of all descriptions were distributed to the men waiting for the arrival of the Chinese. Women turned out in hundreds to incite their menfolk against the Chinese. That morning one thousand men, accompanied by troops of women and children and inflamed by the fire-bells ringing out the alarm as well as by stirring music from the brass bands, erected barricades at the junction of the Ballarat and Clunes Roads to stop the Chinese coaches. Ploughs, drays, timber, stones and bricks were used. As soon as the Chinese coaches came within distance, a hail of stones and bricks fell upon the occupants. The police tried gallantly to protect the Chinese and restore order, but all in vain, as the miners, ably assisted by their better halves, who shouted and cursed and swore and cast stones with the best of the men, compelled the Chinese to retrace their steps back to Ballarat, to the cheers of the victors in this battle for Clunes. Before returning to work the miners again declared their determination to oppose the introduction of Chinese labour in the mines at Clunes. The Australians might not have been capable of creating a Paris Commune, but they were capable of defending the slogan ‘No Chinamen’.”

As Heathcote points out, this bears the hallmarks of a labour dispute rather than a race riot — over issues not dissimilar to current union objections to the use of 457 work visas to import cheaper labour from overseas. ‘The townspeople,’ he writes, ‘had more direct, more pragmatic economic and religious motives for obstructing the coaches from entering town.’

As at the related and, probably, motivating strife at Stawell several weeks before when European blacklegs from Ballarat were likewise assaulted and repelled, the Clunes miners were seeking to protect livelihoods. They wanted to ensure that wages were not driven down, that working hours were not extended, and that the sanctity of the Sabbath was preserved.10

This interpretation is supported by labour historians like Edgar Ross, who write that ‘A miniature ‘Eureka Stockade’ in December, 1873, contributed to the militant spirit of the period.

This occurred during a strike of Clunes miners for the right to have Saturday afternoons off. The Clunes Miners’ Association under the presidency of the Mayor of Clunes, W. Blanchard, erected barricades of timber and stone to bar the way to five cartloads of scabs recruited by the Lothian [sic] Mining Company and being escorted by police. About 1000 unionists and a contingent of irate women assembled, and the scabs and the police were forced to retreat to Ballarat. The Clunes action is generally regarded as providing a stimulus for the formation in 1874 of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association with a constitution to cover all miners in Australia and New Zealand.11

In this description Ross doesn’t mention the ethnicity of anyone involved. How then to explain the ‘Mongolian Octopus’ as the result of working class pressure? If anti-Chinese racism did not come from the working class, then it must have come from the upper echelons. If racism was elite-driven, then it correlated with other contemporary racisms in functioning as what US historian Frank Van Nuys describes as a ‘national safety valve’ — one that had functioned historically to neutralize capitalist class antagonisms.12

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Van Nuys explains, westward expansion into North American frontier territory had given rise to a strong feeling that the United States was a classless utopia. As the availability of frontier territory fell into decline, however, a marked increase in labor struggles put paid to this illusion.13 Nativism and white supremacist ideology picked up the slack, providing a safe outlet for passions that otherwise threatened to undermine the stability of the system, diverting them safely onto a scapegoat whose sacrifice saved the class relations that produced it. Another US historian, David Roediger, explains the ‘national safety valve’ in terms of a comment from famed black abolitionist W.E.B. Du Bois regarding a ‘public and psychological wage’ paid to white majorities amongst subject classes.14 Such privileging of dominant ethnicities offset resistance to class rule through the age-old strategy of divide and conquer. This sought to take advantage of a great truth about nationalism and racism from Arthur Schopenhauer, who wrote, ‘Every miserable fool who has nothing at all of which he can be proud, adopts as a last resource pride in the nation to which he belongs; he is ready and happy to defend all its faults and follies tooth and nail, thus reimbursing himself for his own inferiority.’15 For those who had nothing left other than the false pride of things they had no say in, such as the color of their skin and the geographical location in which they were born, the two were natural refuges, and it was equally natural that they went together in what Roediger calls ‘the wages of whiteness.’16

In the construction of the national safety valve through payment of the wages of whiteness, the suppression of the Eureka Rebellion of 1854 was an auspicious moment, not just for how we remember it long after the fact, but also for its immediate impact — not least for the demonstration effect it might have had for other miners, the rest of the working class, the hyper-exploited Chinese, or indigenous people. As an expression of popular enfranchisement, the Eureka Rebellion was an intolerable threat to the project of empire building. As in other parts of the British empire, the deployment of ‘whiteness’ in elite-driven anti-Chinese propaganda opened the ‘ideological safety valve’ by pitting colonial subjects against one another according to the time-honored strategy of divide and conquer. The problem of working conditions amongst gold miners that gave rise to the rebellion against onerous taxes remained after 1854, but with the memory of the violence metered out to rebellious miners in Ballarat hanging over their head, white miners had plenty of encouragement to accept the bribe of the wages of white privilege as the carrot to the stick of open violence and compulsion in the stead of social justice. Race riots throughout Victoria leading all the way up to Federation, when the first piece of legislation was the act that became known as the White Australia Policy, were a price that had to be paid.

In this presentation I have tried to demonstrate that racism has played a vital institutional role in the development of Australian anglo-capitalism as the national safety value. Just as this has in the past been the case, it continues to play a critical institutional role as a means of blame shifting and dodging of accountability for institutional injustices stemming from colonialism more broadly. The current state of Australian political consciousness appears to reflect the continuing need for national safety valves, the recent re-elected Pauline Hanson especially indicative of that fact. In this way, as we celebrate the Eureka Rebellion, we betray its legacy with racist scapegoating narratives that represent the whiteness carrot to the stick of the state violence used to suppress it in the first place. The same authoritarianism continues to stifle social, economic and environmental justice into the present, enabled by the national safety valve.

Ben Debney is a PhD candidate in International Relations at Deakin University in Burwood, looking at moral panics and the political economy of scapegoating. Originally from Ballarat, Ben was taken to Sovereign Hill on school trips on numerous occasions, but still knows next to nothing about the history of the local indigenous population.

Bibliography

‘Lambing Flat Riots,’ The Argus, Melbourne, Wed 10 Jul 1861, 6, via http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5701829, accessed 4 July 2016

‘Riot at the Buckland,’ The Argus, Thursday, 9 July 1857, http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/7135014, accessed 4 July 2016.

John Connor, The Australian Frontier Wars, 1788-1838. UNSW Press, 2002.

Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, (ed.) Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1997, 4.

Ann Curthoys and Andrew Markus, Who are Our Enemies?: Racism and the Australian Working Class. Neutral Bay, Australia: Hale and Iremonger, 1978.

Charles Ferrall, Paul Millar, and Keren Smith, East by South: China in the Australasian Imagination. Melbourne; Victoria University Press, 2005.

George Fetherling, The Gold Crusades: A Social History Of Gold Rushes, 1849-1929. University of Toronto Press, 1997, 60.

Phil Griffiths, ‘The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888,’ unpublished PhD diss, Australian National University, 2006.

Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Empire: 1875-1914, Hachette UK, 2010.

Christopher Heathcote, ‘Clunes 1873 – The Uprising That Wasn’t,’ Quadrant, 19 February 2009, via https://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2008/12/clunes-1873-the-uprising-that-wasn-t/, accessed 4 July 2016

Bill Hornadge, The yellow peril: a squint at some Australian attitudes towards Orientals. Review Publications, 1976.

Laksiri Jayasuriya, David Walker, and Jan Gothard, Legacies Of White Australia: Race, Culture And Nation, Perth; University of Western Australia Press, 2003.

Sven Lindquist, The Skull Measurer’s Mistake, New York: The New Press, 1997, 5.

Gina Marchetti, Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, sex, and discursive strategies in Hollywood fiction. University of California Press, 1994.

David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness. New York: Verso, 1991.

Edgar Ross, A History of the Miners’ Federation of Australia, Australasian Coal and Shale Employees’ Federation, 1970.

Arthur Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms, London; Penguin Classics, 1973.

Frank Van Nuys, Americanizing the West: Race, Immigrants and Citizenship 1890-1930,, Lawrence; University of Kansas Press, 2002, 11.

Myra Willard, History of the White Australia policy to 1920. Psychology Press, 1967.

1 Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, (ed.) Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 1997, 4.

2 Sven Lindquist, The Skull Measurer’s Mistake, New York: The New Press, 1997, 5.

3 Others took place at Turon (1853), Meroo (1854) Rocky River (1856) Tambaroora (1858) Kiandra and Nundle (1860) and Tingha tin fields (1870).

4 Fetherling, George, The Gold Crusades: A Social History Of Gold Rushes, 1849-1929. University of Toronto Press, 1997, 60.

5 ‘Riot at the Buckland,’ The Argus, Thursday, 9 July 1857, http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/7135014, accessed 4 July 2016.

6 ‘Lambing Flat Riots,’ The Argus, Melbourne, Wed 10 Jul 1861, 6, via http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/5701829, accessed 4 July 2016

7 Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Empire: 1875-1914, Hachette UK, 2010.

8 Christopher Heathcote, ‘Clunes 1873 – The Uprising That Wasn’t,’ Quadrant, 19 February 2009, via https://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2008/12/clunes-1873-the-uprising-that-wasn-t/, accessed 4 July 2016

9 Phil Griffiths, ‘The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888,’ unpublished PhD diss, Australian National University, 2006.

10 Christopher Heathcote, ‘Clunes 1873 – The Uprising That Wasn’t,’ ibid.

11 Edgar Ross, A History of the Miners’ Federation of Australia, Australasian Coal and Shale Employees’ Federation, 1970.

12 Frank Van Nuys, Americanizing the West: Race, Immigrants and Citizenship 1890-1930,, Lawrence; University of Kansas Press, 2002, 11.

13 Van Nuys, Americanizing the West, ibid. The Haymarket Massacre of 1886, the Pullman Strike of 1894, and the Lawrence Bread and Roses strike of 1912 amongst others.

14 David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness. New York: Verso, 1991.

15 Arthur Schopenhauer, Essays and Aphorisms, London; Penguin Classics, 1973.

16 Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness. op. cit, 11-13.

Discover more from Ben Debney

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.